Fatigue

How do I know its Post Viral Fatigue and not just normal tiredness?

Post-Viral Fatigue is when you have an extended period of feeling unwell and fatigued following a viral infection. It is a normal bodily response and is the most common symptom associated with Long Covid.

Fatigue is the most common debilitating symptom that is experienced in long COVID. It is often described as an overwhelming sense of tiredness which can be physical and mental.

Fatigue stops people from returning to work, cooking/planning a meal, holding and understanding a conversation and playing with their children.

The following section will help you understand and manage your fatigue.

- Activity-induced tiredness

- Occurs after over-exertion

- Can occur as a result of poor sleep

- Usually alleviated by rest and recovery

- Usually short-lived or temporary

- Does not usually limit normal day-to-day activities

- Extreme exhaustion and weakness

- Disproportionate to previous activity

- Can occur after minimal effort

- Unresponsive to rest

- Prolonged and fluctuating

- Limits usual activities

How will Post-Viral Fatigue affect me?

Fatigue is unique to each individual; it is often complex and difficult to measure or define. It can range from being mild to severe; have both mental and physical effects; and be very unpredictable and fluctuating.

Physical Fatigue:

Some people find that when they are fatigued their body feels overwhelmingly heavy and that moving at all takes an enormous amount of energy. It may be that specific muscles such as those in your hands and legs fatigue very easily and this can depend on the activity that you are doing e.g. writing, walking.

Mental and cognitive fatigue:

Many people find that when they are fatigued it becomes difficult to think, concentrate or take in new information and that memory and learning is affected. Some people find even basic word finding and thinking difficult.

The fatigue people are experiencing with long COVID leaves them exhausted after completing the most basic of tasks, and some people wake up feeling as tired as they did when they went to sleep.

Fatigue affects people in different ways, and it may change from week to week, day to day or hour to hour. It may also mean people have little motivation to do anything because 24 they are so tired and/or know that undertaking the smallest task will leave them exhausted.

This can make it difficult to explain to family/friends/colleagues. Helping others to understand your fatigue and how it impacts on you can make a big difference to how you cope with and manage your fatigue.

Relaxed tummy breathing

- Make sure you are in a comfortable position with your head and back supported and your shoulders and upper chest relaxed.

- Place one hand on your tummy – feel your tummy rise and expand as you breathe in and relax back down as you breath out.

- Rest and wait for your next breath to come.

- Breathe gently when practicing; there should only be a slight movement of your tummy at rest.

- Overwhelming tiredness and exhaustion

- Weakness with heaviness in limbs

- Reduced energy levels

- Reduced stamina and exercise tolerance

- Joint/muscle pain

- Nausea/dizziness/headaches

- Sweats/chills

- Palpitations/fast heart rate

- Sore throat/swollen glands

- Flu-like symptoms

- Post Exertional Malaise (“PEM”)

- Low mood and reduced motivation

- Anxiety

- Heightened emotions

- Low sex drive

- Reduced confidence

- Feeling useless or hopeless

- Feeling guilty

- Reduced tolerance

- Irritability

- Social withdrawal or isolation

- Mental Fatigue (“Brain Fog”)

- Difficulty concentrating

- Difficulty thinking or processing new

information - Difficulty with planning and/or problem

solving - Short Term Memory Loss

- Speech problems – slurring of words

- Word finding and conversation difficulties

- Disturbed Sleep Pattern

- Reduced appetite

- Burning sensation to skin

- Heightened sensitivity to noise/light/touch

- Heat sensitivity

- Reduced quality of life

- Reduced function and inability to resume previous roles

- Inability to return to work

Managing Post-Viral Fatigue

At present there is no known cure or treatment for Post Viral Fatigue. There is unfortunately no quick fix and a return to normal health can take time. The best way to manage Post-Viral Fatigue is through awareness, pacing and lifestyle changes. Understanding fatigue and how it affects you will allow you to have better control. In addition, by recognising what exacerbates or triggers your fatigue will allow you to be able to better manage this.

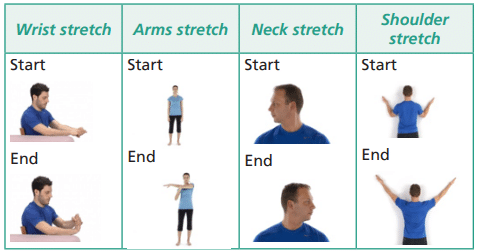

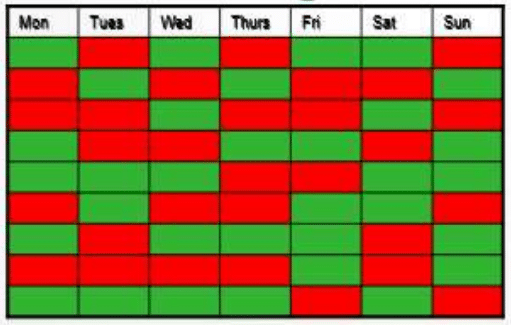

The first step to managing fatigue is being aware of its cycle. Typically, people with Post-Viral Fatigue will follow a pattern known as the BOOM BUST Cycle.

The BOOM BUST cycle is detrimental to your recovery. As the cycle repeats itself, your overall capacity for activity becomes less, meaning your recovery may take longer. During the BUST phase, you usually experience a period of prolonged rest and inactivity which can lead to

deconditioning. Deconditioning can include a reduction in strength, stamina, exercise tolerance, bone density, motor control, flexibility and overall energy production in the body, meaning that daily, routine activities will require increasingly more energy. Recognising your own individual pattern of BOOM BUST can help you to break it.

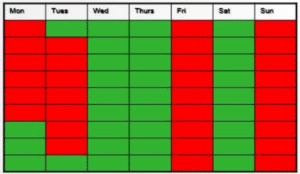

This is an example of a typical BOOM BUST week:

During a BUST phase you may experience what is known as Post-Exertional Malaise (known as PEM) which is a flare-up of symptoms. PEM is the cardinal symptom of fatigue and tends to occur when you have exceeded your current capacity and/or energy expenditure.

PEM tends to be delayed and usually presents itself around 24-48 hours after exertion. It will often require several days of recovery (BUST).

It is important to try to minimise Post Exertional Malaise, as much as possible, as BUST periodsoften include prolonged periods of inactivity leading to further deconditioning.

The best way to minimise PEM is by staying within what is called your energy envelope.

A healthy person will usually have unlimited daily energy levels, however for a person with post-viral fatigue, energy levels may be significantly less than before.

Your ‘energy envelope’ is the amount of energy you have available to use per day – this will be different for everyone.

There are several different analogies which can be used to explain what is meant by the term ‘energy envelope’:

- Money – Picture your energy as money! Each day you get a set “allowance” to spend. Any over-spending will put you into debt meaning you will be borrowing from tomorrow.

- Fuel – Think of a car – it’s engine can only run if the fuel tank has enough petrol in it! When it runs out of petrol it will break down.

- Battery Power – When you buy a brand new iPhone, the battery tends to last all day. When it gets a bit older however, or it gets damaged, the battery will run out more quickly and it will constantly need to be re-charged.

Analogies can be useful for a person with fatigue when thinking about managing daily energy expenditure. Where can you or make savings? How can you keep your tank from becoming empty? What can you do to re-charge your battery?

You can find your own energy envelope, and baseline level of activity, by using an Activity Diary.

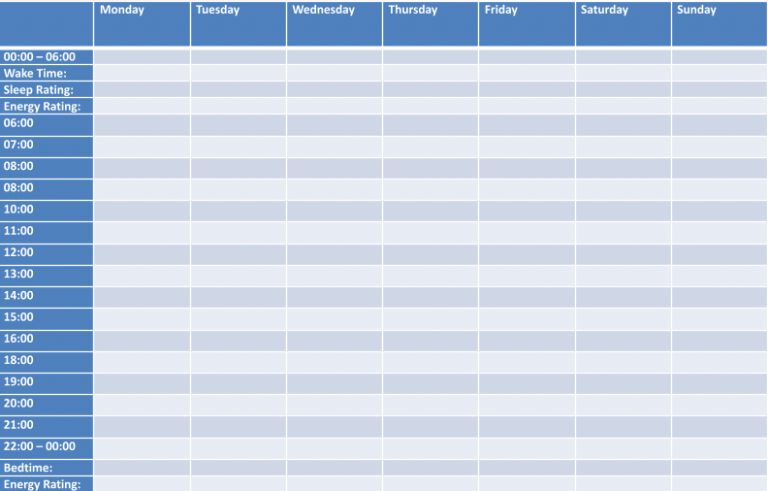

Using an Activity Diary

By using an activity diary, this will be enable you to make a note of everything you do on a daily basis and also make you aware of any patterns and triggers associated with your fatigue.

Start at the beginning of each day:

- Write down each activity including rest period you have taken in each three hour interval.

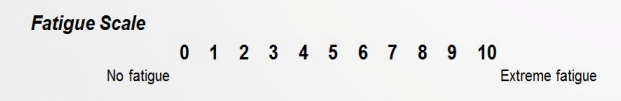

- Using the fatigue scale, below score how you felt at the end of this three hour period.

- Record any other factors you feel are relevant e.g. stressful events, skipping meals, over-exertion.

- Record your BORG score for each activity you undertake. Sometimes, activities that have a high BORG score do not have a high fatigue score.

These are examples of an activity diary:

A typical activity diary can be used to record: your sleep pattern; your morning/evening energy levels (out of 10); the different types of activities that you have completed throughout the day; and how fatigued you feel after each one using the Fatigue Scale below:

A response of 0 would indicate that you do not feel at all fatigued after an activity; and a response of 10 would indicate that you feel totally fatigued and exhausted.

It can also be helpful to keep a note of your daily symptoms; alongside your activity diary.

When you are ready, you can gradually increase the amount of activity you are doing but be careful not to build up too quickly. As a general rule it is suggested an increase of no more than 20%.

Once you have made an increase, you will need to keep the levels stable for around a week before increasing again.

Once you have completed a week’s worth of diaries you should be able to notice any BOOM BUST patterns; what constitutes a good day or a bad day; the different type and levels of activity that fill your week; the different type and level of exertion that causes the most fatigue or triggers PEM; how often you are resting and re-charging; how often you are moving around; how you aresleeping; and how the types of environments that you have been in have contributed to your fatigue.

By recognising how different types and levels of exertion make your feel after completion, it can allow you to identify specific patterns. This allows you to better manage your time and energy and puts YOU in control.An activity diary is also a useful tool to find your baseline and/or energy envelope.

Establishing a baseline level of activity is important before introducing any further activity or exercise.

Once you have completed some activity diaries, you should be able to see what your triggers are; look at what changes you can make; and find a level of activity that can be achieved consistently everyday whilst avoiding BOOM BUST and PEM.

When establishing a baseline, it is important to remember that your activity levels may be significantly less than they were pre-Covid. Remember that you are now working with a different post-viral body and there is no limit to the time your body may take to heal. It is likely that you will have good and bad days due to the fluctuating nature of post-viral fatigue, however finding a baseline level of activity that you can achieve consistently, whilst reducing BUST days and minimising your overall Post Exertional Malaise levels, will help in the long term. Once you are aware of your baseline level of activity, it is important not to be attempted to do any extra, even if you are feeling well. Post Viral Fatigue cannot be pushed or worked through.

A good way to manage your daily activities is by finding a mid-point of activity that is achievable on both good and bad days. On bad days you should avoid under-exertion and on good days you should avoid overexertion – all the time ensuring a good balance between activity and rest (PACING) and ensuring a safe level of activity that does not exacerbate your symptoms.

The overall aim is to reduce the BOOMS and BUSTS. Start low and go slow, know when to stop and aim for gradual reconditioning.

Recognising your triggers

It can often be challenging knowing when to STOP! Most people often only stop at the point where they feel they can no longer continue or when they are already experiencing an increase in their symptoms. This means relying on your body to tell you to STOP!

Imagine you are in a car and the car needs to stop to prevent it from hitting a brick wall. You would need to apply the brakes before hitting the wall. With fatigue, you need to stop before you reach the point of over-exertion (the wall), even if you still feel well.

Exertion can be defined as anything that stresses or strains the body. The body can be exerted in many different ways, and it is important to look at which type(s) of exertion contribute to you feeling fatigued and experiencing PEM. Identifying these triggers is vital to recovery. Keeping an activity and/or symptom diary can help you to become more aware, however when completing diaries and making a connection between over-exertion and PEM, it is important to note that PEM can be delayed by 24-48 hours.

Some different types of exertion include:

- Physical Exertion – physical activity, exercise

- Orthostatic Exertion – standing for long periods of time

- Cognitive Exertion –reading, writing, watching tv, using a computer, scrolling through your phone

- Social Exertion – attending meetings, long conversations or challenging social interactions

- Sensory Exertion – loud repetitive noises, bright or flashing lights

- Emotional Exertion – stress, arguing, tragic events

- Environmental Exertion – proximity to allergens, temperature, changes in weather/season

In addition to different types of exertion, there are also different levels of exertion – HIGH, MODERATE and LOW. Each activity that you do will use a different amount of energy.

Daily activities don’t tend to be carried out in isolation and your day may consist of a combination of tasks which use varying levels of energy. Mixing different types of activity and exertion throughout the day can help to maintain energy levels. Being aware of the types and levels of activity you are completing and how you are exerting your body allows you to become more aware of what you are doing. It is important to look at how you can split up your activities to maintain a balance of different types and levels of activity/exertion throughout the day, and to also recognise when and how to rest and re-charge afterwards.

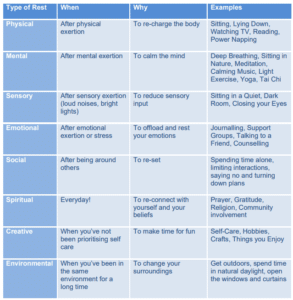

Resting, relaxing and re-charging are an extremely important part of managing fatigue. Good quality rest and relaxation is vital to re-charge your body’s energy and healing. Relaxation is also important as it can help to calm your body down when it is stressed which, in turn, supports regulation of your body’s autonomic nervous system (the system which controls breathing and heart rate).

You should acknowledge rest and relaxation as part of your daily schedule and plan rest breaks, up to 30 minutes long, in advance where possible. Regular rest should be taken before you become tired and even if you are feeling well – remember the ‘stopping distance’ analogy.

For some people, resting is simply sitting and watching television or scrolling through their smartphone however, it is important to not just rest the body, but the mind and senses too. The type of rest and re-charge that you need will depend on the area of the body that has been exerted.

When managing fatigue, it is important to ensure you are taking frequent re-charge breaks throughout the day in between activities. This is known as PACING.

Whilst activity and exercise are important to regain and maintain muscle strength and endurance; with fatigue, exercise should be safe, balanced, gentle and within your limitations. Vigorous exercise, or anything that triggers PEM, is not recommended!

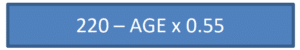

As the goal of PACING is to minimise PEM, it is important to find a consistent level of activity that is manageable for you, whilst keeping your expectations low. The simple rule is: if you are experiencing PEM then you are doing too much. You cannot push through your fatigue. Any activity which sends your heart rate above your anaerobic threshold has been shown to trigger PEM therefore you should aim to stay at around 55% of your Maximum Heart Rate (see below) when completing activities or exercise, in order to avoid or reduce PEM.

You should aim for a gradual and flexible return to normal day-to-day activity initially and then only when you feel your fatigue is improving should you try a small amount of light activity followed by REST. The aim is to work on (1) frequency; (2) duration and then (3) intensity. Start low and go slow!

Remember: If you don’t overdo it on good days, you will avoid the severity of symptoms on bad days.

What is PACING?

PACING is an evidence-based technique which has been proven to manage and support recovery from Post-Viral Fatigue.

PACING, in terms of managing fatigue, means finding a balanced and achievable pattern of activity and rest in order to break the BOOM BUST cycle and to minimise PEM. It means staying within your energy envelope and current capabilities and slowing down to work at a steadier pace instead or pushing or rushing.

This is the pattern of a typical PACED week:

PACING will enable you to expose your body and mind to daily demands in a regular and controlled way in order to maintain a consistent and realistic daily routine and help the body stabilise itself.

Pacing is a strategy that helps you to get out of this boom and bust cycle and helps you to manage your activities without aggravating your symptoms.

You should develop an activity plan which allows you to stay within your current capabilities and therefore avoid ‘overdoing things’. Your levels of activity can then be increased in a controlled way over time as your stamina

By pacing your activities you are ensuring that:

- You are controlling the demands you place on yourself

- These demands are in line with your current capabilities

- You are exposing your body and mind to these demands in a regular controlled way

- Use an activity diary to analyse your day-to-day activities.

- Find your baseline (usually a mid-point between a good and bad day).

- To being with, strip back anything that is not essential.

- Alternate between different types of activity and exertion throughout the day.

- Aim for a range of high, medium and low energy activities throughout the day.

- Split up any complex or high energy activities.

- Ensure regular rest, relaxation and re-charge after each activity. Remember to rest your mind and senses as well as your body.

- Remember to stop before you become tired!

- Prioritise uplifting, inspiring and enjoyable activities that provide you with a sense of achievement; help you connect with what is important to you; and boost your mood.

- Work through high levels of fatigue very gently with the aim to minimise Post Exertional Malaise. If you continue to develop PEM you may have to continue to decrease your activity until it is no longer induced. Listen to your body.

- Ensure a period of consistency (at least 7 days) before very slowly and gradually increasing activities and/or exercise. Start low and go slow.

When using PACING; it can also be helpful to look at PLANNING, PRIORITISING and POSITIONING.

When planning your day or week, spread your activities out rather than trying to fit them all in one day. Think about when your energy levels may be at their best and therefore completing high energy tasks at this time.

Can an activity be graded so that it doesn’t have to be completed all at once? E.g. cleaning one room as opposed to the whole of the house.

Before starting an activity, it is useful to think about what you may require to complete that particular activity. It is helpful to have an organised working space and ensure that you have all items to hand to avoid you having to use more energy going back and forth.

Can you conserve energy by sitting down to complete some of the tasks? E.g. preparing vegetables for cooking.

As well as planning your activities, it is equally as important to plan your rest and relaxation times to allow you to ‘recharge.’

Creating an activity diary or a daily plan will help you to pace yourself and prioritise what you want and need to do. It may take a few attempts to get right, but once you feel you have found your baseline it is important to ensure a period of consistency before this is increased again.

Planning is a powerful self-management skill which puts you in control. It allows you to:

- Plan ahead/pre-plan activities

- Schedule in rest breaks

- Identify and make time for what is important to you

- Minimise the frequency of activities

- Spread out activities or split them into more manageable stages or chunks. Does the level

of activity exceed your current limitations? - Think through your activities – can they be done in a different way? Find easier ways to complete activities (short cuts) to conserve energy

- Schedule more difficult tasks for when you have the most energy Everyone has a time of day when they are most alert

- Alternate between light and heavy tasks

- Alternate between cognitive and physical tasks

- Make time for fun

Prioritising allows you to prioritise, not just what is necessary, but what is most important to you. It may also be useful to identify what activities in your day are necessary, i.e. which tasks ‘need’ to be done and which do you ‘want’ to do, what activities could be carried out at a different time or day, and which activities could somebody else assist with. Prioritising activities is very individual and what may be a priority for some may not be for others.

These are some things to consider:

- What is a priority for YOU?

- List your weekly activities in order of importance. Focus on the week ahead only – next week can wait (for now).

- Apply the 4 Ds to your list: Do? Delay? Delegate? Drop?

- Identify necessary tasks. Is it necessary? What’s the worst that can happen if it’s left undone?

- Eliminate any unnecessary tasks – let go of the things you can’t do.

- Is there anyone else who can help? Can you ask or hire someone to do some of your tasks for you?

- Can you schedule some time for the things you enjoy every day. What else can wait?

- How can you save energy for the things you want and need to do?

Tip: It may be useful to write down the activities that you both want and need to do throughout the day. You could then score these activities to help you to prioritise them. This will also help you in planning your day.

- Use your environment to support you… lean, sit, perch, rest where possible.

- Avoid pulling, lifting, twisting, bending, stretching and overhead reaching.

- Avoid prolonged standing, squatting or stooping.

- Use gravity and momentum to decrease your workload – push and slide rather than lift.

- Maintain a good posture, where possible.

- Avoid prolonged gripping.

- Bend and use leg muscles when lifting – stand close to objects.

- Avoid lifting children – sit them in your lap instead.

- Use feet to close doors/drawers.

- Bring feet/knees up to put on socks/shoes to avoid over-bending.

- Have work in front of you, not to one side to avoid twisting.

- Don’t hold your breath during a task.

- Inhale during the lightest part of an activity and exhale during the most strenuous part.

- Keep your chest and open and relaxed.

- Use breathing techniques such as pursed lip breathing; diaphragmatic breathing and ‘Blow as you Go’. Your Physiotherapist can teach you these techniques.

When PACING, it is useful to pay attention to your surroundings and become aware of how certain environments contribute to your fatigue.

- Reduce clutter – busy environments can contribute to fatigue (and both mental and physical tasks can require more energy when navigating clutter).

- Ensure adequate room temperature – increased body temperature can increase fatigue.

Shivering also uses energy. - Ensure adequate ventilation – a supply of cool, fresh air will help with fatigue.

- Ensure adequate lighting – poorly or brightly lit rooms can strain the eyes and cause sensory overload.

- Reduce noise/distractions – too much noise, or too many distractions can contribute to

sensory/mental fatigue. - Lack of sunlight/daylight – lack of Vitamin D can cause fatigue; and lack of natural melatonin can affect sleep and contribute to fatigue – open the curtains, get outside, spend time in nature.

It is important to look at different ways to save energy. This can be achieved by:

- Making simple adjustments to your daily routines to improve your energy efficiency.

- Saving energy for things that are important to YOU!

- Activity Grading (see below).

Understanding the different component parts of an activity and how to break an activity down into more achievable steps is a process known as activity grading. Learning new ways to complete activities helps you to use your energy more wisely. By using activity grading, this can help you to:

- Find the easiest way of doing a task so that you have energy left over afterwards

- Break down activities into smaller, more achievable stages by adding, reducing or

eliminating steps - Change your position regularly, and add in regular rest breaks

- Learn to use equipment and/or the environment to support you

- Seek assistance with activities

- Slow down your pace

Your Occupational Therapist can provide further advice around Energy Conservation and Activity Grading; along with advice on and provision of equipment, aids and adaptations.

Making Lifestyle Changes

A lack of sleep or poor sleep quality can make fatigue worse.

Sleep can be adversely affected by a number of things:

- Pain

- Needing the toilet

- Insomnia

- Spending more time than usual inside

- Too much caffeine

- Alcohol

- Noise

- Temperature (too warm or too cold)

- Mood (anxiety/depression)

- PTSD and flashbacks

When thinking about your sleep and the effect it is likely to be having on fatigue it is important to consider each of these issues and make any necessary changes to minimise the impact.

Impaired sleep is common in those who have been medically unwell and those who are experiencing stressful circumstances. Poor sleep habits and sleep deprivation can contribute to and exacerbate both physical and mental fatigue.

Managing your sleep is therefore important in managing Post-Viral Fatigue.

- Getting good quality sleep can help your body to repair and recover.

- Aim to keep to your regular day and night-time routines where possible.

- Aim to spend some time in natural daylight/sunlight during this day. This supports production of melatonin (the sleep hormone).

- Aim for 8-9 hours sleep per night.

- Daytime naps should be limited to 30 minutes maximum. Naps should not be taken after 3pm.

- Ensure good sleep hygiene as far as possible – speak to your Occupational Therapist for more details and/or referral to Salford’s Sleep Hygiene Programme.

- Insomnia is common in Long Covid. If this, or any other sleep disturbance is an issue, speak to your GP.

- If you struggle with over-thinking and inability to relax; it may helpful to empty your mind and relax your body before sleeping using relaxation, deep breathing, journaling or meditation techniques. Further Psychological support may also be beneficial.

Food is fuel. Nutritional deficiencies can contribute to and exacerbate fatigue.

- Try to eat a well-balanced, healthy diet to give your body the nourishment it needs to return to good health.

- Both physical and mental fatigue can occur as a result of nutritional deficiencies.

- Limiting or skipping meals can cause fluctuations in blood sugar/glucose/energy levels.

- A healthy balanced diet supports optimal immune function.

- Try to keep your BMI within a healthy range – between 18 and 25. Being overweight can contribute to inflammation which stresses the body and rapidly uses up nutrients.

- A healthy balanced diet should include: High intake and variety of plant-based foods such as plant and animal proteins, vegetables, fruits, wholegrains, beans, nuts, seeds and legumes; Moderate intake of seafood, lean meats and dairy; and low intake of processed or refined foods – high sugar, salt, animal/trans fats, overly processed bread or pasta, junk

foods and fast foods. - You can take a regular probiotic supplement to support your immune health.

Experiencing Post Viral Fatigue and a delayed recovery from Covid can have a profound impact on you, your personal life and roles, your work life and your usual day to day routine. It is natural to feel upset, frustrated and, sometimes guilty, however it is important to continue to look after your mental well-being and seek support when required, as stress, low mood and anxiety can all exacerbate fatigue.

You may find PACING difficult to maintain if you are feeling low in mood or lacking in motivation; and this is understood and expected. Bad days are expected; do not worry. The process of PACING can be trial and error even for someone who is fully committed but it can be helpful to remember that even 1% progress per week adds up to 52% over a year! The important thing is to try to do what you can, when you can, as much as you can, in order to regain some degree of control.

It can be helpful to identify any mental health or stress related triggers so that you can reduce or avoid these or seek support to manage them. You should also try where possible, to include social, emotional and mental rest into your daily routine and also use relaxation techniques and coping strategies where possible.

Lastly, it is important to prioritise enjoyment in order to boost your mood and, in turn, your energy levels. You should also try to stay connected to others where possible and avoid isolating yourself. There are several Long Covid support groups available across Salford which you can be linked in with.

If you are experiencing stress, anxiety or low mood that is having a profound effect on your life and/or recovery then you should speak to your GP or Therapist who can arrange for further help and support.

Recovery Tips

- Complete an activity diary in order to identify your triggers.

- PACE – start low and go slow. Balance activity with rest.

- After an activity; aim to re-charge the area that has been exerted. Limit rest breaks and daytime naps to no more than 30 minutes. Avoid under-exertion.

- Escape the BOOM BUST Cycle. Reduce your triggers and avoid any over-exertion.

- Aim to minimise PEM where possible.

- To begin with, aim to stay at 55% of your maximum heart rate (220 – your age x 0.55).

- Find your baseline and ensure a period of consistency before attempting to increase your activity levels.

- PLAN – spread out your activities throughout the week; and alternate between different types of exertion. Remember to schedule in rest breaks.

- PRIORITISE – Get rid of anything unnecessary and ask for help. Try to balance enjoyable tasks with not so enjoyable tasks and make time for what is important and

enjoyable to you. - Aim to conserve energy where possible.

- Optimise Sleep, Diet and Mental Health. Stay connected and seek help and support where necessary.

- Expect stumbling blocks and setbacks. Fatigue is fluctuating in nature and recovery will therefore be trial and error. Remember to PACE even on the good days.

- Manage the factors you can do something about. Remember – small gains add up to improvement (even 1%).

- Aim to keep activity levels stable for at least 7 days. Once the foundations are in place you can then move into the building phase.

- Aim to resume your normal daily routine by making small, gradual changes. Increase activity levels by no more than 20% per week. Do not rush your recovery or try to push through your fatigue.

- Set yourself SMART goals (specific, measurable, achievable, realistic and timely). These can be short or long term goals. What do you want to achieve?

- Record and reward your achievements and progress.

Remember:

Recovery varies from person to person and it can take time.

It is important to focus on how far you have come; not on who you were pre-Covid.

Resources

Disclaimer: This video has been created for a Cambridge and Peterborough audience so please ignore any references to the local service, instead use the content appropriately for your own care.

Thank you to the contributors for this section